John Law

James Buchan

John Law

A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century

Author’s Note

In John Law’s lifetime, two principal calendars were in use in western Europe. The Roman Catholic countries as well as the Netherlands, Denmark, the German states and Switzerland used the Gregorian or New-Style calendar, while England, Ireland and Scotland persisted with the Julian or Old-Style calendar, which was eleven days in retard. Colonies used the calendar of the metropolis.

The date given in the text is always the date current at the place in which the incident occurs or the letter is written. Where there may be confusion, as in correspondence between Paris and London, or on shipboard, two dates are shown in this form: October 11/22, 1720. The Gregorian is always the later of the two dates.

In Great Britain and Ireland, the new year began on March 25. In the text, it is assumed the year began on January 1. In the notes, letters dated from those countries in the winter months are shown thus: A to B, January 1, 1720 [i.e. 1721].

C’est bien domage quil nest pas que bornee letandue enfinie de son imaginations car il a de grande calitee il est perdue par un trop grand hidee de luymemes .

(It’s a shame really that he did not once place limits on his boundless imagination for he has something great about him. He has perished for too grand a conception of himself.)

ELEANOR DE MÉZIÈRES

Chapter One

Lotteries and Other Games

Nota: seijds een Schotsman van Edenburg te wesen . (Note: Is said to be a Scotsman from Edinburgh.)

BURGOMASTERS OF THE HAGUE

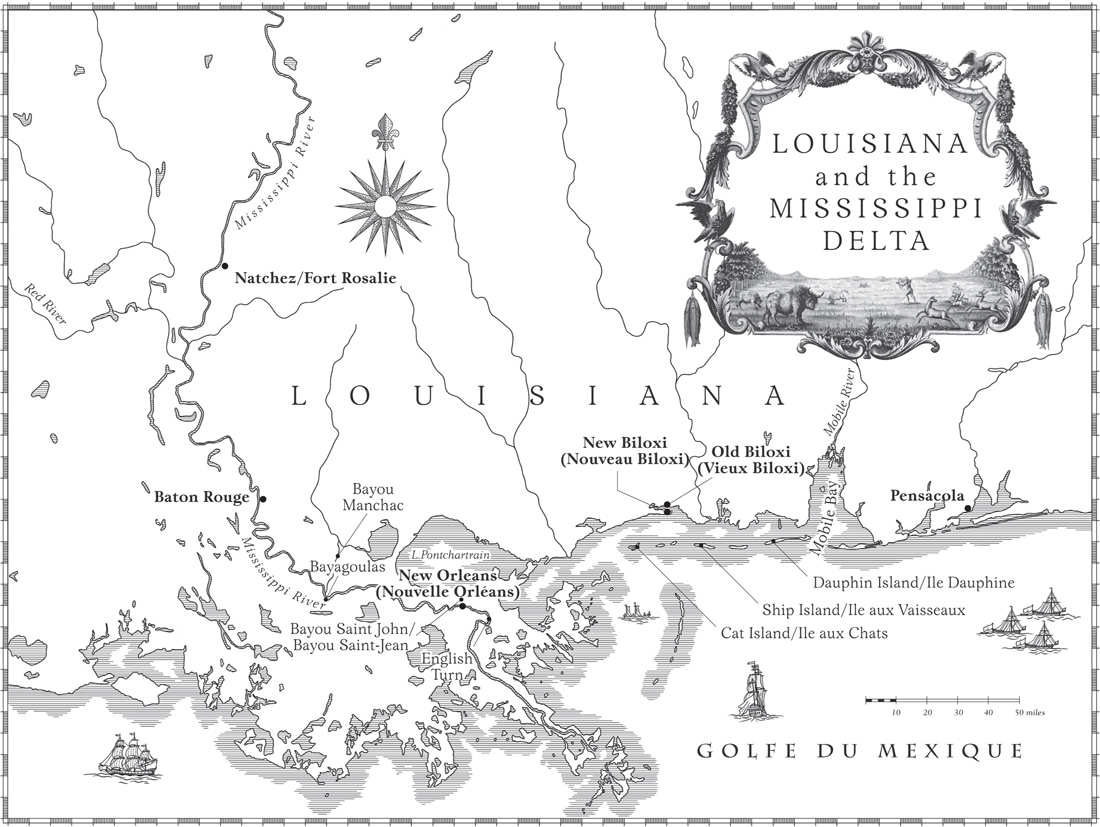

The marquis d’Effiat, Charleval and Toucy, comte de Tancarville and Valençay, chamberlain and hereditary constable of Normandy, baron de La Rivière, seigneur de Gerponville, Saint-Suplix, Roissy, Orcher and Guermantes and proprietor of Arkansas in the New World, also de Ferry, Dujardin, Annington, Wilmot, Hamilton, Gardiner, Hamden and, in the Jacobite cipher, 888.75.1804, was born in the year 1671 in the Parliament Close of Edinburgh, capital of the Kingdom of Scotland.

He was baptised John in the church of St Giles, a few feet from his cradle, on April 21 of that year. 1

His father was William Law, master goldsmith. His mother was Jean Campbell. John was their first son to survive. In all, William Law and Jean Campbell had twelve children, of whom four died in childhood and were buried in Greyfriars churchyard in an angle of the city walls to the south. 2

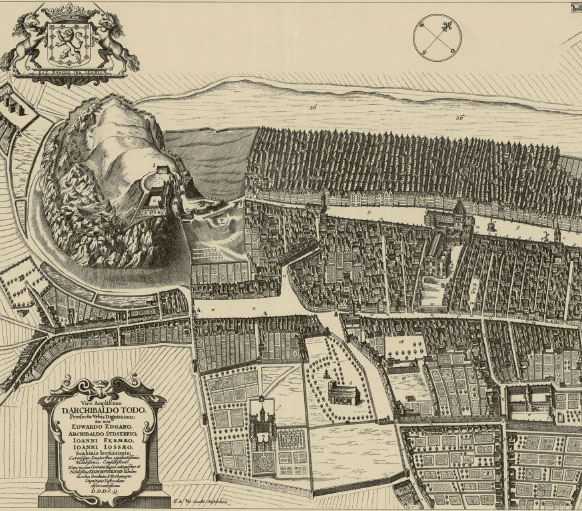

In the year of John Law’s birth, Edinburgh was a crowded stone town of some 30,000 inhabitants. Described in a debate in the Parliament at that time as “the most unwholesome and unpleasant town in Scotland”, 3 Edinburgh clung within its defensive walls to the debris of an extinct volcano. A broad street ran down a mile from the castle in the west to the palace of Holyroodhouse in the east and the aristocratic suburbs of the Canongate. To the north and south, the town halted at precipices. About halfway down the High Street on the south side stood the gothic High Church of St Giles, and behind it a square or close in front of the Parliament House of Scotland. It was against the south wall of the church that William Law probably had his workshop, and there, above the shop or in a tenement nearby, John Law was born. 4

The Scotland of that time was in ferment. In the sixteenth century, the Roman Catholic Church in western Europe disintegrated, and reformed or Protestant faiths became established in Switzerland and Bohemia, the Baltic territories, parts of Germany and France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, England and Scotland.

Though united under a single crown since 1603, when James VI of the Scottish ruling house of Stuart succeeded Elizabeth on the thrones of England and Ireland, those countries were at odds over religious practice and how their Churches should be governed. The Church of Scotland, which was Presbyterian in character and drew its inspiration from John Calvin’s Geneva, rejected the Anglican institution of bishops. On such matters hung the salvation of the whole world.

In the course of the 1630s, the animosity of the two Protestant Churches broke out into warfare. The Presbyterians objected to the wish of King Charles I and Archbishop William Laud of Canterbury to impose on Scottish congregations the English prayer book. In 1638, an open-air meeting in Greyfriars Churchyard launched a National Covenant to protect the Presbyterian Church. The consequence was a war that engulfed England, Scotland and Ireland, and in 1649 cost King Charles his head.

The regicides, under Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, established a republic or Commonwealth in which Scotland lost its independent Church, its laws and parliament. After Cromwell’s death, the triple monarchy was restored in 1660 under Charles’s son, Charles II, and Scotland recovered its institutions, but that brought no peace to the Church. Many Presbyterian ministers, particularly in the south-west of Scotland, rejected the authority of bishops over parish elders or kirk sessions and took their flock into the fields. One of the witnesses at John Law’s baptism, his grandfather Mr John Law, who succeeded his own father as minister at Neilston, near Paisley in the west of Scotland, was turned out of his parish in 1649 and may have decided that the reformed Church was too precarious a living for his sons and grandsons. 5

Goldsmithing in Edinburgh was a profession protected by craft exclusions and the patronage of the town, Church and Parliament. To align the practice of the Protestant Churches in his kingdoms, King James I/VI sponsored an Act of the Scots Parliament in May, 1617 to oblige Scottish parish churches to use “bassines” “lavoiris” (jugs) and “coupes” for the two sacraments, Baptism and Holy Communion, in the manner of English parishes. 6 That law made the fortunes of several master goldsmiths in Edinburgh.

William was apprenticed goldsmith just after his brother John in 1650, 7 and received the right or freedom to practise the craft in March 1662. William Law’s “assay” or masterpiece consisted of “ane silver coupe with ane cover graven and ane voupe”: that is, an engraved silver cup and cover and a wedding ring. 8 About that time, William set up shop, at a rent paid to the town of £40 Scots per year or about three pounds and six shillings sterling. 9

He had married, on the day after Christmas of 1661, Violet or Violat, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a brother-goldsmith, George Cleghorne, and Helen Wilson. 10 The marriage did not long last. Violet died in giving birth to a son, named after her father, and was buried in Greyfriars on October 18, 1662. 11

William mourned his wife for a year and then, on October 22, 1663, at St Cuthbert’s Church under the castle, married for a second time. 12 No doubt he needed a mother for the infant George. His second wife was Jean Campbell. Jean or Jeane, who was baptised on August 13, 1639, was one of four daughters of James Campbell, a merchant of Edinburgh, and his wife Isobell Orr. All four girls made good marriages in or around the Parliament Close. Agnes, the oldest, married Andrew or Andro Anderson, appointed in 1671 the King’s printer in Scotland; Jean married William Law, master goldsmith; Isobell the merchant John Melvill; and Beatrix Archibald Hislope, bookseller in the Close.

They were forceful women in the old Scots style. As widows, Agnes, Jean and Beatrix managed their husbands’ businesses. Agnes became notorious for her ruthlessness. After her husband’s death in 1676, to all intents insolvent, she enforced his monopoly of printing Bibles, New Testaments, Acts of Parliament and other authorised texts and defended it in the Scottish courts for nearly forty years, though her productions were riddled with blasphemous misprints.

Since every literate family in Scotland had been required since 1581 by Act of Parliament to possess a Bible and psalter, hers was a rewarding business and she died in 1716 as Lady Roseburn with a fortune of £78,197 Scots or about £6,500 sterling. 13 Her principal rival, James Watson, wrote of her printing works in the College Yards: “In fine, nothing was study’d but gaining of Money by printing Bibles at any rate, which she knew none other durst do, and that no Body could want [was permitted to be without] them.” 14 She is said single-handed to have postponed the Scottish Enlightenment fifty years.

Those four women and their husbands hung together. Archibald Hislope and John Melvill stood witness at John Law’s baptism. If they had a recreation, it was a cause at law.

At his first wife’s death in 1662, William had silver and gold stock in the shop of 700 merks or £466 Scots, and an estate net of debt of £260 Scots or £22 sterling. 15 With Jean Campbell’s help, he prospered. He took his first apprentice, John Calquhoun, in 1666, 16 and in 1670 rented a second shop from the town to accommodate his expanding trade. 17 In 1675 and 1676, he served as deacon of the Incorporation of Goldsmiths or leader of the craft.

There is a picture of an Edinburgh goldsmith’s shop of the seventeenth century. In 1624, George Heriot, the third of his line to be admitted to the Incorporation in 1588, left some £24,000 sterling to endow a charitable orphanage just outside the city walls which exists as George Heriot’s School to this day. A sandstone frieze of about 1630 above the north door of the school shows the interior of a goldsmith’s shop from the generation before William Law.

Heriot is shown working his bellows before a furnace. Beside it is an anvil. To the right is a work bench, with two scalloped work positions with leather bags beneath to catch the silver scrapings, and above it a tool bar of hammers, pincers and dies. To stand before this antiquated frieze, and then think of John Law’s plans for the Paris stock exchange and his colony of Louisiana is to feel the horizons recede and a new world open up to view. In no other life of the time, except that of Captain James Cook in his dormitory in Whitby, does a small beginning become so enlarged.

There survive from William Law’s shop communion cups and baptismal basins at the kirks or churches of North Leith, Aberlady, Ballingry, Culross, Gamrie, Glencorse, Kilwilling, Kinglassie, Lauder, Midcalder, Stirling St Ninians, Salton and Yester. 18 His finest sacred work is the Murray Cup, presented by Anne Murray, Lady Halkett, to the College of St Leonards at St Andrews University in 1681 in gratitude for her son’s good report from the regents or professors. It is eight inches tall, eight inches across the bowl and five inches across the foot. This communion cup, made by William and his apprentices between 1679 and 1681, John Law would have seen and handled.

William’s profane pieces pass at high prices through the saleroom. In the course of the wars of mid-century, Covenanting committees had power to gather in “all siler worke and gold worke in Scotland” outside the churches and turn it into coin to pay soldiers and munitioners. As John Law was to write in the only one of his works printed in his lifetime, Money and Trade Considered , “The plate at the restauration [1660] was inconsiderable, having been called in a little time before.” 19

The plate melted down had to be replaced. William’s hallmark, which consists of a crown and the initials “WL”, can be found on table pieces such as the stemmed shallow dishes known as tazzas, the bowls called porringers, two-handled cups (quaitches) and the little silver spoons with their pairs of initials that bridal couples liked to order on a trip to town. There is also an invoice, to one David Pringill in 1679, where in return for 37 ounces of “broken silver” and £25 14s. Scots in cash, William and his apprentices made a watch-key, a ring setting, a plain ring, a dozen flowered spoons and a “Shewgar Castor”. 20 By 1705, Scotland’s treasure of profane silver was estimated at £150,000 sterling. 21

At some date no later than 1674, William followed George Heriot into the business of banking. Just downhill from the lock-up goldsmiths’ workshops or “buithes” against the walls of St Giles, the town’s trade was conducted at the Mercat or Market Cross. The goldsmiths were needed to assay or verify the muddle of Scots, English, Dutch and other foreign coins that turned up in trade, to provide safe deposit for coins, jewellery or bullion, and to lend their own money or clients’ deposits at interest to finance agriculture, commerce or simple expenditure.

Lending, even for the small sums involved, was more remunerative than smithing. According to John Law himself, the “fashion” or what the goldsmith charged as his fee over and above the precious metal in a piece amounted to a sixth, or a 20 per cent premium. 22 William Law lent money at between 6 and 8 per cent per year. He was also engaged, from at least 1676, in victualling drovers to take Highland black cattle to England for the London beef market. In an inventory of assets later drawn up for John Law, there is a debt remaining from that year from two Highlanders, Alexander McMilland and Donald McNeill, “drobers”, of £1,000 Scots. 23

By 1681, William had outgrown his shops. On May 26 of that year, he signed a contract with Robert Mylne or Milne, the Master Mason to King Charles II, and Andrew Patersone, former deacon of the Incorporation of Wrights in Edinburgh, to build a “tenement and fabric” (workshop) on the “east side of the entry to the Parliament House”. In the ashlar building, with six storeys and a basement on the Close side and two basements on the slope, William was to have two shops, with iron-bound doors and windows of Newcastle glass, well-seasoned wainscoting, seasoned deals for flooring, chimneys and cellars. As his share of the enterprise, William was to pay £334 and twelve shillings sterling in four instalments. 24

Mylne was the principal developer in Edinburgh of that period. The “great stone tenement and land” was damaged on February 3, 1700, when fire broke out in the closet window of a certain John Buchan at the top of the Meal Market, and fanned by a wind from the south-west, engulfed the east side of Parliament Close. The high-flying kirk ministers saw that as judgment on the wicked men who dared to raise such “Babels”. 25 The building was destroyed by a second fire in 1824, but one of Mylne and Patersone’s schemes from 1690, known as Milne’s Court, a small open square of sixand seven-storey tenements on the north side of the Lawnmarket above St Giles, exists to this day. Those apartments, now fit only for college students, were none the less an advance on their predecessors and commemorate both the prosperity and overcrowding of Edinburgh at this time.

As William’s business grew, so did his family. His first child with Jean, Isobell, died in 1664 and was followed to Greyfriars burying yard the next year by his son by Violet Cleghorne, George. Of the surviving children, Agnes was born in 1666, Jean in 1669, John (1671), Andrew (1673), William (1675), Robert (1678), Lilias (1680) and Hugh (1682).

John Law’s childhood passed under a pall of religious anxiety. On May 3, 1679, a band of Covenanters waylaid the coach of James Sharp, Archbishop of St Andrews, on the road from Edinburgh and assassinated him. Rebellion spread across lowland Scotland. King Charles II sent north his illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth, who defeated the Covenanters in a pitched battle at Bothwell Bridge in Lanarkshire in June. To enforce royal and bishops’ rule in Scotland, Charles in October despatched his brother and heir, James, Duke of York, to Edinburgh as Lord High Commissioner.

James had converted to the Roman Catholic faith and that May a bill was introduced in the English parliament to exclude him for that reason from succession to the throne. The crisis gave rise to the aboriginal division in British politics between the exclusionist Whigs and loyalist Tories, which survived, in ever-changing complexion, for two centuries. King Charles dissolved Parliament and sent his troublesome brother north, but James was no more welcome among the Presbyterians.

Robert Law, a kinsman of William’s and minister at Easter Kirkpatrick in Dunbarton, reported that on Christmas Day, 1680, the College boys at Edinburgh made an effigy of the Pope, his belly stuffed with gunpowder, carried it in procession up Blackfriars’ Wynd and burned it in the high town, which “the Duke of York took ill, being then in Abbay of Halyrudhous”. 26 The appearance of two blazing comets over the town, Kirch’s or C/1680V1 that December, 1680 and Halley’s in August, 1682, compounded the anxiety as being, in Mr Robert’s words, “prodigious of great alterations, and of great judgements on these lands and nations for our sins”. 27

James did succeed on his brother’s death in 1685 to the throne as James II of England and VII of Scotland, but that provoked a rebellion in Scotland by the Earl of Argyll, which was suppressed. James was ejected three years later by a conspiracy of English parliamentarians and the Dutch stadtholder or chief magistrate, William of Orange-Nassau, who was married to James’s Protestant daughter Mary. James’s adherents, who followed him into exile in France or lay low in their shops or on their estates, became known as “Jacobites” after the Latin for James, Iacobus. Many families hedged their bets, with one branch opting for James and another for William.

Some authors say that John Law attended the Edinburgh High School. This claim appears in a nineteenth-century history of the school 28 and cannot be true. In the two hundred or so of John Law’s letters seen by this author, as well as his manuscript memorials to princes and parliaments, there is not one word of Latin or scripture. In his writings in French, Law makes small mistakes that he would not have made had he known the Latin grammar underlying that language. John Law could not have attended the best grammar school in the British Isles without learning something of the humanities.

On September 9, 1679, at the age of eight, he was apprenticed to his father. 29 Unlike his younger brothers Andrew, apprenticed in 1694, and William (1703), John never passed master or received a hallmark. It was not until October, 1719 that the Town Council granted its prodigal son the freedom of Edinburgh, together with a Burgess Ticket in a gold box costing £127 16s. 3d. sterling and a giddy letter. 30 At some time in his childhood and youth, John Law contracted smallpox, which was by no means unusual.

In the summer of 1683, William bought the estate of Lauriston and Randleston on the estuary or firth of the River Forth just to the north of Edinburgh. The seller was Margaret Dalgliesh, daughter of Robert Dalgliesh, a lawyer who had served both King and Commonwealth, and Jean Douglas. In the deeds, which were confirmed by King Charles II and registered on August 10, 1683, William provided that after his death and that of Jean, who would enjoy the rents during her lifetime, the estate was to go to his eldest surviving son, John Law. There is no mention of the sum paid.

The estate consisted of an oblong stone tower house, built at the end of the sixteenth century by Sir Archibald Napier of Murchieston or Merchiston and by then inconvenient and old-fashioned, and fields and pasture stretching down to the shore of the Firth. The house, which was given to the city of Edinburgh in 1926, has been much altered over the years. To see it as William Law and Jean Campbell saw it in June 1683 it is necessary to screen out a nineteenth-century wing and garden, and some municipal paraphernalia, while preserving the cattle in the pasture and the redshanks whistling from the Firth. The ghost of Scots wizardry haunts the stone, composed of a Napier horoscope on the south front, an anagram Dalglish and Douglas over the south door, and a secret chamber reached by a tiny stair.

In a survey of the parish of Cramond conducted in 1630, the fields of Lauriston were valued at 142 bolls of bear and 50 bolls of oats and oatmeal or about 20 to 25 tons of grain. 31 (Bear is an ancient variety of low-yielding barley still grown by crofters in the Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland.)

In buying the estate, William did not abandon business. The castle bears no trace of William or John Law or Jean Campbell, and there is no record that any of them lived there. William had few months to live anywhere. On July 25, 1683, “being necessarly called to goe furth of this kingdom”, William drew up his will and set off from Edinburgh.

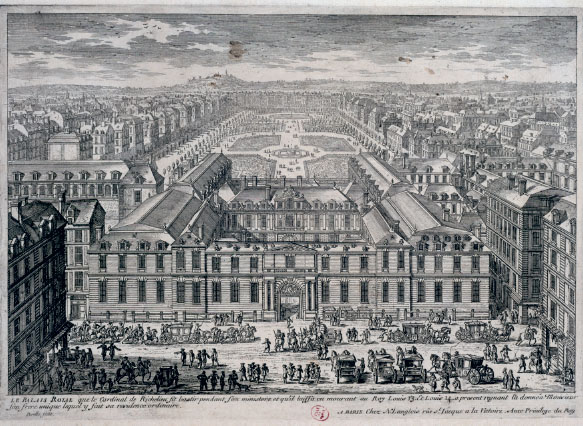

John Fairley, who was commissioned by the owners of Lauriston Castle in the early twentieth century to collect materials on the Laws, surmised that William travelled to Paris for surgery to remove kidney stones, a disease that by reason of the high-protein and low-fibre diet of the age was prevalent. A dynasty of barber-surgeons in Paris, the Colot or Collot family, had for a century specialised in an operation to cut out calculi from the urinary tract, and surgery was also offered at the poor hospitals of the hôtel Dieu and Charité. The fame of the Collots drew patients from all over Europe, including Scotland. In the Gordon Papers in the Register House in Edinburgh, there is a letter of 1709 in which one Robert Colinson asks Father Lewis Inese or Innes, the superior of the Scots College, the old Roman Catholic seminary at the university of the Sorbonne in Paris, to give the bearer Lord Huntly “that rare and wonderfull gravell stone left by me at your Colledge tuentie years agoe”. 32

If Fairley’s is a true conjecture, the operation was a failure. In the register of William’s testament, made on August 15, 1684, William is described as “deceast in the moneth of [blank] 1683 years in the Kingdome of ffrance”. Though a Protestant, he was still a Scot and was buried at the Scots College. There are impulses to action that never reach the conscious mind, and it may be that John Law was drawn to Paris by his father’s tomb. He later made a donation to the College of fifty of his company shares, worth at their peak more than £30,000 sterling or many millions today. 33

In his will before leaving Edinburgh, William charged Jean as principal guardian (tutrix sine qua non ) “during her widowitie” and six tutors “to uplift the soumes and @rents * [capital and interest] due to my said eldest sone John, and to educat him and the remanent [remaining] children at schools and trades as they shall think most convenient.” The tutors comprised William’s brother John, goldsmith; Isobel’s husband Melvill; Beatrix’s second husband Robert Currie, stationer; Jean’s cousin Robert Campbell; and the attorney Hugh Maxwell of Dalswintoun. 34

The property included the insight and plenishing (furniture and stock) of the shop and house, valued at £3,333 Scots, and bonds, mortgages and invoices, including arrears of interest, of £25,832 Scots, making a total of £29,165 or about £2,500 in the sterling of the period. The loans, at annual rates of from 6 to 7.5 per cent, were to the best-known families and most solid risks in Scotland, including the Duchess of Hamilton, the Marquesses of Douglas and Huntly, the Earls of Argyll, Annandale, Atholl, Balcarres, Breadalbane, Dundonald, Forfar, Kintore, Roxburgh and Seaforth, the Goldsmiths’ Incorporation (1000 merks) and the towns of Jedburgh and Cupar. The principal debtor was Charles, Earl of Mar, owing 7,000 merks principal or about £390 sterling. William had become a substantial banker, among the most substantial in town outside the high nobility, and a prosperous man. John Law was served heir to his father on September 25, 1684. 35

Jean did not marry again. A new husband would gain rights over her property and might interfere with the children’s estate. Her widowed sister Agnes, who remarried in 1681, obliged her new husband, Patrick Tailfer, to forgo his husband’s right or ius mariti over “the printing irons, and other estate” in return for a dowry of £10,000 Scots, and still had to go to court against his creditors. 36 After Beatrix died in 1687, her children’s tutors sued her second husband, Robert Currie, for mismanaging their inheritance. 37

William Law’s goldsmithing fell to his second son Andrew, then apprenticed to his uncle John Law. In 1687, a contract with Mylne and Patersone provided Andrew with the south half of the fourth storey of the “new great stone tenement”, with five rooms and a cellar below the scale stairs. 38 As for the banking business, Jean was not above having a debtor consigned to the Old Tolbooth prison beside St Giles’s kirk. 39 In the nine years after her husband’s death, she doubled the loan book, both in her own name 40 and that of her eldest son John. 41

That son was proving a handful. The historian Robert Wodrow, who wrote an account of the persecution of the Presbyterians under the Stuarts, came across the young John Law at school in the west of Scotland in 1683 or 1684. After Bothwell Bridge in 1679, Wodrow’s father James, a candidate for the ministry and a strong Presbyterian, had taken refuge in his native village of Eaglesham, about ten miles south of Glasgow, “a very retired corner”, where his family joined him in 1680. The minister of the village, James Hamilton, who was permitted to preach under the so-called Act of Indulgence of 1669, managed a small grammar school.

“I mind [remember],” Robert Wodrow wrote in a life of his father, “among the scholars at that school, there was one about the 1683 or 4, John Law, son to a goldsmith at Edinburgh, whom his father sent to Eglishame, both to be removed from the temptations of Edinburgh, and to be under the care of Mr Hamilton, who was nearly related to him, and to be under my father’s inspection who was pretty nearly related to him.” 42

Though Wodrow was a small child in 1683, there is reason to trust his recollection. On April 4, 1684, John Law’s elder sister, Agnes, married Hamilton’s only son, John, who had just been admitted as a Writer to the Signet or attorney at law in Edinburgh. 43 John Law was by then about thirteen years old, an age at which in the next generation the philosopher David Hume was leaving Edinburgh University. It is strange to think of this hulking youth in the manse schoolroom with the five-year-old Robert Wodrow. William Law, or Jean Campbell, must have been desperate.

John Law’s mental ornaments as a man, his grasp of mathematics, music and painting, his fluent French and Italian, and his good manners, were not to be acquired in the Scotland of the late seventeenth century. He did learn to write. As an adult, John Law wrote in the modern Italic script, but his writing, though legible, retains some peculiarities of the Scottish Secretary hand taught in the previous century: an e that resembles the Greek theta, and a superscript mark like a first-quarter moon or reversed c to distinguish a u from an n .

In 1686, back in Edinburgh, John reached his legal puberty and agreed to accept Jean as his curatrix or guardian. Then, at the end of 1687 or the beginning of 1688, mother and son quarrelled so comprehensively that the sixteen-year-old John left home or Jean turned him out of doors. John refused to sign receipts for payments of interest on the loans and mortgages Jean had out in his name. He also sued her under a so-called Writ of Aliment, that then and now in Scotland requires a parent or guardian to support a child. So much can be deduced from Jean’s rejoinder or protest to the Court of Council and Session, the highest civil court in Scotland. 44 This is the voice of Jean Campbell:

Jean Campbell, relict of the deceast William Law Goldsmith burgess of Edinburgh and curatrix [guardian] to his children and whith whom they are appointed by the father to remayne in famillie with me ther mother during their minoritie to be educat and alliemented [supported]: that where John Law my eldest sone without any offence or provocatione has laitely deserted my famlily, contrair to the will of his father and as I am informed has given in ane petitione to your Lordships craving ane aliement to be modified by your Lordships to be payed to him by me

Against which it is humbly represented that therecan be no aliement modified or payed to him by me

1mo/ because I am willing to aliement him my selfe in my familly with the rest of his brethrene and sisters as I have done hitherto since the father deceise [father’s decease] and which is appoynted by his fathers last will

20/ it is most just that he should returne to my familly, not only, because of his said father’s will but also that I may have the better opportunitie to oversee his behaviour night and day, that it be blameless and deceint. which is my great designe according to the trust repoised in and by his father And the trew cause of his deserting of my familly, was because of my motherlly reprehending him for bydeing late out at night and goeing to the Lotterie and other Ghames And

30/ ther can be no aliement allowed by the mother to him because he being yet minor and not yett seventeen years and she his Curatrix and he reffuses to subscrybe recepts with me aither for @rents or stock so that I cannot lift money to pay aither aliement to him or the rest of the childrene as instruments taken upon his said reffusal produced heare. Theirefore I humbly beseech your Lordships to take the premises to your serious consideratione and to reffuse the said John Law his said petitions and to ordaine him to returne home againe to my familly where it shall not be questioned but that he shall be aliemented and cloathed as becomes his fathers son And in the meantyme that your Lordships will be pleased to ordaine him to subscrybe recepts and discharges for money as occasion affords and your Lordships please. 45

There was no licensed lottery in Edinburgh until 1694 but that does not mean there were not unlicensed lotteries. As for the “other ghames”, it was said Law was an expert player of the sport then known in Scotland as catch or cache, and today as real or court tennis. William Tytler of Woodhouselee, a lawyer-antiquary, told an Edinburgh audience just before his death in 1792: “I have heard that the famous John Law of Laurieston . . . and James Hepburn, Esq. of Keith, were most remarkable players of tennis.” 46 Another lawyer, Sir David Dalrymple, raised to the Court of Session as Lord Hailes, reported that Law “addicted himself to the practice of all games of skill, chance, and dexterity and was noted as a capital player at tennis, an exercise much in vogue in Scotland towards the close of the seventeenth century.” 47

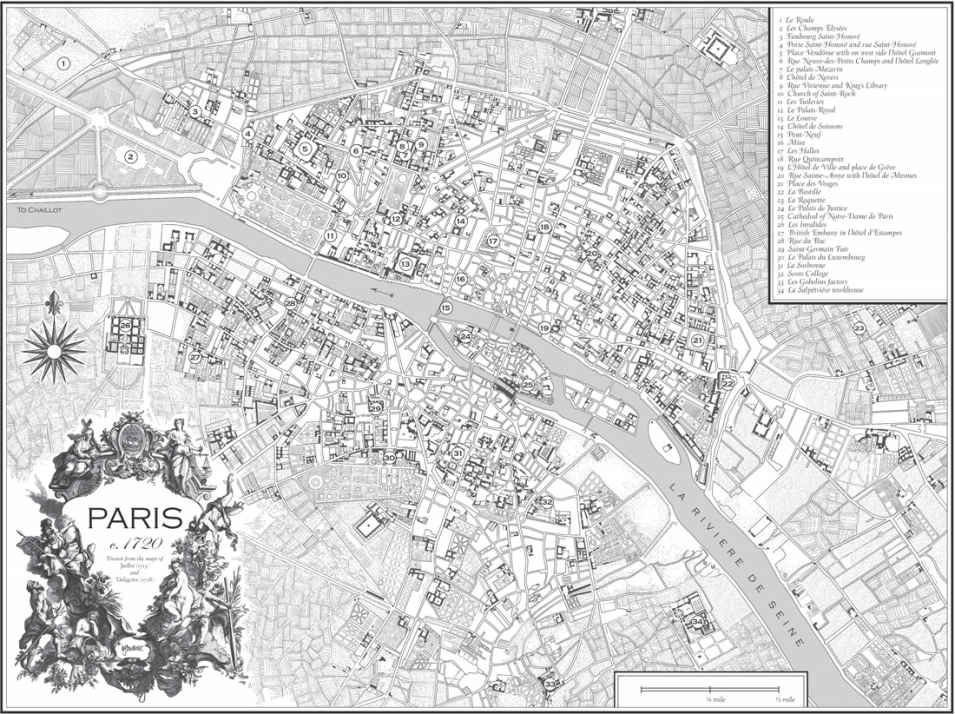

Those witnesses may be quoting the same source, but may also convey the ruins of a fact. Tennis had been brought over to Scotland from France in the sixteenth century. A court built for James V in 1539 at Falkland Palace in Fife is in use today. There was also at least one tennis court in Edinburgh, just outside the Water Gate and opposite the main front of Holyroodhouse. A warrant, signed by King Charles I at Windsor on July 15, 1625, instructed John Erskine, 2nd Earl of Mar and Lord High Treasurer of Scotland to pay £50 to the mason, Alexander Peeres, as the price of the court. 48 It is shown and labelled “31” on Gordon of Rothiemay’s map of 1647. Tennis was scarcely likely to please the Presbyterians, but between 1679 and 1682, James, Duke of York and his daughter Anne had revived a number of aristocratic pastimes, including tennis and drama, in the Scottish capital. The court was in use as both a tennis-play and a theatre till at least 1710, after which at some point it became a linen works.

Like other sports at that time and in the eighteenth century, such as horse racing, prize fighting and cricket, tennis was principally an occasion for wagering. Today, real-tennis players are handicapped like race horses so that the outcome is uncertain and a skilful player may still be beaten by a novice. There is another small piece of evidence. In 1728, in Venice, the French legal philosopher Charles-Louis de Montesquieu interviewed Law. He wrote up longhand notes of the conversation, during which Law used a term from real tennis to describe the treachery of a man he trusted: faux-bond or “false bounce”, where the ball comes off the court walls or penthouses at an unexpected speed or angle. 49

On February 16, 1688, the justices of the Court of Session referred both John Law’s petition and his mother’s response to one of their number, Lord Harcarse, “with power to him to determine them as he finds just & in case of difficulties to report”. 50 That was Sir Roger Hog of Harcarse, who passed advocate 1661 and joined the bench as Court of Session Justice or Senator in 1677. In fact, Harcarse was ousted from Court of Session a month after Jean’s petition by King James II and VII, in one of the King’s last acts before he himself was chased from his three kingdoms by Dutch William and Mary Stuart in what became known as the Revolution.

The case never proceeded to full court, and was settled, but it took several years. There is evidence that John Law was planning to leave Scotland in 1690, and on April 22 of that year appointed a factor or agent, the writer or attorney James Marshall, to manage his affairs and collect rents while he was abroad. 51 On July 1, Marshall and Jean Campbell recovered an old debt of John, Lord Bargany of £1 in money. 52 John Law did not go abroad, for he was still in Edinburgh on his twenty-first birthday two years later.

At issue was not the estate at Lauriston, of which Jean had the liferent or use and profit during her lifetime, 53 or the shops in the Close, but how the bonds or loans should be divided between John, on the one hand, and on the other Andrew, William, Robert, Hugh and Lilias. (Agnes and young Jean had received their inheritances of respectively 10,000 merks and 8,000 merks at their marriages in 1684 and 1688). 54

On July 27, 1689, John Law obtained a so-called Decreet of Compt and Reckoning at the Burgh Court of Edinburgh which required his executors to account for and pay out the money due to him. Jean transferred to him bonds valued at £31,759 18s. 4d. Scots. After more to-ing and fro-ing by the lawyers, Jean handed over the writs for bonds totalling a further £25,600 Scots. Those included the £1,000 Scots borrowed in 1676 by the Highland cattle drovers.

Finally, on April 16, 1692, on or soon after his twenty-first birthday, in the presence of John Hamilton, WS, husband of sister Agnes, Hamilton’s servant George Carson, and John Murray, writer in Edinburgh, “me John Law of Louristoun” pronounced himself “fullie satisfied” with his tutors and mother in the administration and care of his estate, and discharged them. 55 Then, with his boats damaged but not entirely burned, and furnished with securities offering an uncertain income of £200–£300 sterling a year, John Law set off for London.

In those days, people did not like to travel far alone. A kinsman of Law’s on his mother’s side, John Campbell, who had been apprenticed in Edinburgh (to the master goldsmith John Threipland) in the same year as Law, 56 had a design to set up in London as a goldsmith-cum-banker to the London Scots. His business was to have much to do with John Law and eventually became the long-lived bank, Coutts & Co.

John Campbell is first listed in London as paying contributions to the poor or “rates” in the parish of St-Martin-in-the-Fields for a property on the south-east side of the Strand between the modern Craven and Hungerford Streets, on June 20, 1692. 57 It is likely the two young men and brother apprentices sailed south from the Port of Leith in each other’s company.

Chapter Two

A Money Business

In englandt soll es nicht so schimpfflich sein gehengt zu werden als In franckreich undt teutschlandt .

(In England to be hanged is apparently not the disgrace it is in France and Germany.)

ELIZABETH CHARLOTTE D´ORLÉANS 1

London dominated Great Britain at the end of the seventeenth century more than today, for there were then no manufacturing cities in the Midlands and North. With 600,000 persons, London was twenty times the size of Edinburgh. Scots were bewildered and intimidated, as King James I and VI in 1616: “All the countrey is gotten into London; so as with time England will onely be London, and the whole countrey be left waste.” 2

The capital of England had three parts. Between the court city of Westminster in the west, with the royal palaces of St James’s and Whitehall and the Parliament, and the commercial city in the east with its port and dockyards, the intervening fields of Middlesex were being built over. Noblemen’s houses were thrown up, and just as soon torn down and replaced by tenements for merchants and gentry, in the manner of a modern city that is simultaneously built and destroyed.

The town was at war. The snag or drawback in inviting Dutch William in 1688 to occupy with Queen Mary the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland was war with the Jacobites. That consisted, in its first episode, of uprisings in support of King James in both Ireland and the Scottish Highlands, which ended with the massacre of the Macdonalds at Glencoe in February, 1692. It was also a share in William’s quarrel with Louis XIV of France, the richest and most powerful ruler in Europe. The phase in that conflict known as the Nine Years War, or in North America as King William’s War, began in 1688 and deployed English forces not only on the sea, where they felt at home, but on continental soil in the southern or Spanish Netherlands.

One consequence was to draw enlisted men and officers into the capital, where they camped in Hyde Park, on Blackheath or on Hounslow Heath, and gamed and brawled in the streets and taverns of Covent Garden in Middlesex. The practice of duelling, which had arrived from Italy in the sixteenth century, had been suppressed under the Puritan Oliver Cromwell but had broken out again at the restoration of the Stuart kings in 1660. For the diarist Samuel Pepys, writing in 1667, duelling on petty quarrels had become “a kind of emblem of the general complexion of this whole kingdom”. 3

In a comedy by Thomas Shadwell presented at the Theatre Royal at the time of John Law’s arrival in London in 1692, The Volunteers , or the Stock-Jobbers , a beau or man-about-town, up to then a poltroon, discovers in himself a taste for duelling, and picks a quarrel with every man he meets. “It’s an admirable exercise! I intend to use it a mornings instead of tennis.” 4

Duels then were not the tournaments of the Middle Ages or the affairs of honour of later years, governed by written codes of conduct and discharged at dawn with pistols in some snowy forest clearing. They were melees with rapiers or short swords in hot or barely cooling blood, sometimes with seconds drawn and fighting, and shading away into assassination and armed robbery. Gentlemen wore swords in public. That showed they were gentlemen. Duels with pistols, which were less lethal, did not come into fashion until the second half of the eighteenth century.

For the common law, the Church of England and civilian London, duels were crimes and gentlemen needed to take themselves to corners of Barnes Common, Barn Elms and Hyde Park or defend their honour amid the rubbish dumps, stables, market gardens and wastes north of Great Russell Street behind the palaces of Montagu House and Southampton House. King William showed no inclination to abate the belligerence of his officers, but rather tolerated it, and duellists condemned to death by the courts received a royal pardon.

Among John Law’s certain acquaintance at this time were two men who fought duels. Richard Steele wounded a brother officer in Hyde Park and later campaigned against duelling in the journals he founded, The Tatler and The Spectator . 5

Elizeus Burges, later British Resident in Venice but then an officer of the Horse Guards, in the space of five weeks killed a gentleman of the King’s bodyguard in Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square) and a stage actor in the Rose Tavern in Russell Street, Covent Garden (now occupied by the Drury Lane Theatre).

To take those men out of the taverns and into the siege trenches in Flanders required money. To protect the land of his birth from French expansion, and pay subsidies to his allies, William needed in the region of six million pounds sterling a year at a time when ordinary taxes and excises produced just two millions.

Unlike the Stuart Kings, who came to grief over money, William had the support of Parliament and the commercial district of London, known then and now as the City. In the course of the 1690s, William’s ministers erected a system of public borrowing which allowed Great Britain to spend far more on the war than it could raise in taxes, and meet France, during a hundred and twenty-five years of intermittent conflict, on equal and then superior terms. Louis XIV did not help his fiscal cause by persecuting the French Protestants or Huguenots, who were active in trade and financial markets. With his revocation of the act of toleration known as the Edict of Nantes in 1685, some two hundred thousand Huguenot craftsmen, merchants and financiers left France for England, Ireland, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, Prussia, Geneva and Switzerland.

In conditions of war, English merchants could not insure their cargoes and, cut off from their European and American markets, and suppliers, found working capital lying idle in their shops. They put it into speculation, or “stock-jobbing” as it was known. That might be in a flurry of joint-stock companies floated to buy some commercial privilege or monopoly from the Crown, or in simple wagers. Daniel Defoe, a good financial mind but always and ever for hire, estimated that “there was not less gaged [wagered] on one side and other, upon the second siege of Limerick [August–October 1691] than two hundred thousand pound.” 6 The coffee houses in Exchange Alley in the City, which served as stock exchanges, dealt in rumour, libel and military intelligence.

William’s ministers sought to capture this spirit of speculation for the war effort.

In those days, English government departments consisted merely of the Secretaries of State and a few clerks. For ideas and policies, particularly in the revenue, they depended on private men or what were called “Projectors”, always, as Defoe wrote, “their mouths full of Millions”. 7 Among their number was Thomas Neale (1641–1699), an industrialist and property developer, who in 1678 bought for £6,000 the court position of King’s Groom Porter. 8 Along with such duties such as having kindling and coal carried to the King’s chamber and privy lodgings, the Groom Porter supervised play at court and resolved disputes at the tables. He also had the power to license all billiard tables, bowling alleys, dicing and gaming houses and tennis courts, from which he profited. Neale was the spit of James II. 9

In 1693, Neale received the right to offer a lottery, comprising 50,000 tickets at ten shillings each, with 250 winning tickets offering prizes from £20 to £3,000. It was copied from a Venetian lottery of the previous year, and caught the imagination of the town. 10 “Now soe it is,” Samuel Pepys wrote to the mathematician Sir Isaac Newton on November 22, 1693, “that the late Project (of which you cannot but have heard) of Mr Neale the Groom-Porter his Lottery, has almost extinguish’d for some time at all places of publick Conversation in this Towne, especially among Men of Numbers, every other Talk but what relates to the Doctrine of determining between the true proportions of the Hazards [probability] incident to this or that given Chance or Lot.” 11

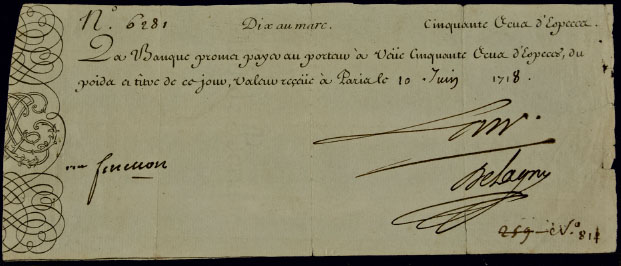

So successful was his own lottery, that Neale persuaded William’s ministers to allow him to raise one million pounds for the war, the so-called Million Adventure. This time it was a lottery loan, somewhat like modern Premium Bonds, in which the money staked is not at risk. The lottery consisted of 100,000 tickets at £10 each, each with the right to an annual payment or annuity of £1 for sixteen years. Of those tickets, 2,500 would offer further annuities for sixteen years, ranging from £10 a year to £1,000 a year. The subscription opened on March 16, 1694 and began to fill.

The lottery tickets, because they carried no person’s name, were commodities and were bought and sold in the Alley and elsewhere long before the draw set for the autumn of 1694. As if the lottery were not risk enough, by at least midsummer people were trading rights to buy or sell the tickets at a certain price. 12 Such contracts are now known as “options”. There is no evidence that John Law was trading in lottery tickets, except that he did so in 1688 and again in 1712, and it is hard to imagine he abstained in the interim, like a smoker in mid-career.

Meanwhile, William’s ministers had become intrigued by a cant phrase in the City, “a fund of Credit”. All that meant was that a secure and reliable revenue from a parliamentary tax or excise over a number of years could be used to pay the annual interest on a loan to the King or, as the term now is, capitalised. On January 12, 1692, the House of Commons appointed a committee of ten men to “receive proposals for raising a Sum of Money towards the carrying on the War against France , upon a Fund of perpetual Interest”. 13

Among the proposals studied by the committee was one from William Paterson (1658–1719), of farming stock in Dumfries, who had traded in the West Indies and the Netherlands. After debate in the committee, and refinement by the Treasury Commissioner Charles Montagu, Parliament in April, 1694 granted the King duties on ships’ cargoes (“tunnage”) and beer and spirits up to £100,000 a year that was sufficient (after management expenses) to pay an 8 per cent interest on a loan of £1.2 million to prosecute the war. (£1.2m × 8 per cent = £96,000 plus £4,000 for management = £100,000.) 14

In return for their money, the subscribers to the loan were allowed to incorporate themselves, in the fashion of the public creditors of the Commune of Genoa, who three centuries before had banded together as the Casa di San Giorgio, or House of St George. Since that name was taken, the London adventurers were to be known as “the Governor and Company of the Banke of England”. They at once solicited deposits from the public, for which the bank issued receipts or “Bank notes” which were used as money alongside coins from the royal mints. The public deposits were then put out in further advances to the King. As Law later wrote, the Bank of England not only helped finance a war but lowered the rate of interest and provided a convenient currency for business. 15

It is frustrating that for Law’s first eighteen months in London, which formed him at a time of life when he was impressionable, there is small information. Certain features of his personality took shape, such as his habit of expressing his opinions as wagers or the fashion in which he tied his tie. In that period, John Law was exposed in the English capital to new ideas about the nature and creation of money, which gave him his occupation in life and which he elevated to a level unimaginable in his father’s shop in Edinburgh.

At that time and for years afterwards, the London Scots kept their own company. At the heart of the Scots colony in London, was the “Scots Box”, a society for mutual aid founded in the reign of James I/VI to assist those countrymen who had come up to London and fallen on hard times, and to give the better-off occasions for good cheer. It survives to this day as ScotsCare.

Granted a royal charter in 1665 as “the Scottish Hospital of the Foundation of Charles II”, the box at once expended all its funds in burying three hundred Scottish paupers in the bubonic plague of that year. By the time of Law’s arrival, the society managed a workhouse or hospital in Blackfriars and included “almost all Scotishmen that frequent London”, with some two hundred and fifty members paying a penny sterling each a week towards the hospital. 16

The members met at Covent Garden taverns, with a quarterly dinner at five shillings and an annual dinner on St Andrew’s Day, November 30. Most of the corporation’s records were burned in a fire at its Covent Garden offices in 1877, but there survives a list made in the 1730s of all contributors up to then. The list includes amid Williamites and Jacobites all mingled together – “tis impossible for this Charity to be of any Party” 17 – John Law with a contribution of fifteen guineas, or £15 15s. 18

Among those Scots, Law would have known his father’s debtors, or their sons, such as John, Earl of Mar (Box donation: £20). He also had an introduction to a merchant at St Catherine Coleman in the City, William Stonehewer (£5), who boasted an estate of some £600 and was to leave his son and daughter at his death in 1698 “moneys bills bonds and parts of shipps and accounts with my household goods rings and apparell diamonds and pearles to be equally divided”. 19

Whatever John Law was doing, it was not enough to cover his expenses. On February 6, 1693, he travelled to the City and signed over the fee or freehold of Lauriston and Randleston to his mother, together with “my seat in the Kirk of Cramond”, in recognition that Jean “hath advanced, paid and delivered to me certain soumes of money as the full availl pryce”. The deed, which was described by Fairley but not found by this author, was witnessed by the merchant Stonehewer and his servant Peter Johnston. 20 By April of that year, John Law had also disposed of the late Lord Mar’s debts to his father. 21

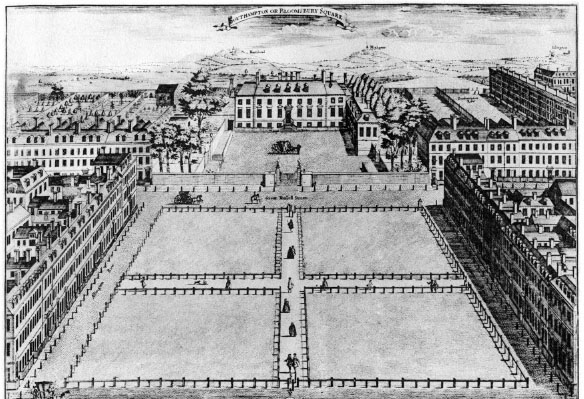

On April 9, 1694, John Law ceased to be obscure. About one hour after noon that Monday, he killed a man in Southampton Square (now Bloomsbury Square), probably at the north-east corner. He was arrested and confined to Newgate, the prison built into the western wall of the City.

Newgate was a fearsome place, violent, dirty and overcrowded, but Law had money or friends enough to secure the best billet. 22 That was in the Press-Yard, a stone-paved open space some fifty-four feet by seven feet, on the east side of the prison abutting the College of Physicians. It formed part of Keeper James Fell’s lodgings and was let out by him for profit. Here a dozen or two dozen prisoners who could pay a “praemium” of at least £20, and a rent of 11s. 6d. a week, were housed in “divers large spacious rooms, which in general have very good air and light, free from all ill smells”, as a later account described them. 23 Law was given the best of them, the “parlor” on the ground floor, “towards the Colledge”, where he had a bed to himself. 24

The next day, April 10, George Rivers, Esq., Middlesex coroner, empanelled twenty jurors to inspect the dead body and determine the cause of death. The inquest identified the body as that of one Edward Wilson. He was a younger son of Thomas Wilson, a London merchant who had bought Keythorpe Hall, near Tugby in Leicestershire, and Anne Packe, daughter of Sir Christopher Packe, who had been Lord Mayor of London under the Commonwealth. Edward Wilson is listed on the monument to the family erected by his elder brother Robert at a cost of £100 in the church of St Thomas à Becket at Tugby. Like his adversary, he was dusty enough from the shop to be playing with swords.

Edward had been an elegant young man, first among the beaux and “mirrour” of the town. London wondered how the younger son of a £200-a-year Leicestershire gentleman had lived for the past five years at a rate of £4,000 or £5,000 a year. 25 As the diarist John Evelyn wrote, Edward Wilson lived “in the garb and equipage of the richest nobleman, for house, furniture, coaches, saddle-horses, and kept a table, and all things accordingly, redeemed his father’s estate, and gave portions [dowries] to his sisters.” 26 Richard Lapthorne, the London newswriter for the Coffin family at Portledge in Devon, wrote to the family on the 14th: “Wilson is the subject of the general chatt of the towne. Hee [was] no Gamster nether was hee known to keepe women company & it canot bee yet discovered how he came to live at so prodigious an extravagancy.” 27

Nobody appears to have remarked on the place of assignation. On the street known as Great Russell Street, Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton, Lord Treasurer, had built on the north side a wide, low house, designed by Inigo Jones, with two wings, a garden behind with views of Hampstead and Highgate hills 28 and a broad square in front. The square, which became known as Southampton Square, was divided into parterres with speculative houses and tenements on the east and west sides and to the south a market, commemorated in the modern Barter Street. Evelyn wrote in his diary on February 9, 1665: “Dined at my Lord Treasurer’s, the Earle of Southampton, in Blomesbury, where he was building a noble square or piazza, a little toune.” By 1694, Southampton Square was a fashionable address. There was no cover of trees or thickets. It was not one of the places listed by The Spectator as “fit for a Gentleman to die in”. 29

The coroner’s jury resolved that a certain John Law lately of the Parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields and the County of Middlesex:

. . . moved and seduced by the devil’s instigation on the 9th day of April in the sixth year of the reign of the King and Queen, by force of arms and in the said parish a certain Edward Wilson, Gent . . . feloniously, of his own free will and malice aforethought made attack and the said John Law with a sword made of iron and steel of a value of five shillings, the same John Law, in his right hand drawn and held and was holding, struck and hit the same Edward Wilson in the lower part of the stomach a mortal wound of two inches breadth from which the said Edward Wilson instantly died. 30

On the following Tuesday, April 17, Law was brought at 7 a.m. to the Middlesex Quarter Sessions at Hicks Hall in St John Street, where he was committed to trial at the main criminal court, next to his prison, the Justice-Hall at the Old Bailey. 31 This was a three-storey building, built in brick in the Italian style to replace the old courthouse destroyed in the Fire of London in 1666, set back from the street behind a yard where witnesses and lawyers liked to congregate. The ground-floor courtroom was open at the front to allow air to circulate and dispel the infections and gaol fevers brought up from Newgate by the prisoners.

The next day, April 18, Law was brought in. The Crown, to make a case against Law of premeditation or “Propense Malice”, read out some letters which had passed between Wilson and the accused about a lady, Mrs Lawrence, “who was acquainted with Mr Lawe”. 32 Law’s letters, which were unsigned (which was not unusual for the period) were “very full of Invectives, and Cautions to Mr Wilson to beware, for there was a design of Evil against him”. There were also two letters from Wilson, one to Law and one to Mrs Lawrence. The court reporter wrote: “Mr. Wilson’s man, one Mr. Smith, swore that Mr. Lawe came to his Master’s house a little before the Fact was done, and drank a Pint of Sack [sherry] in the Parlor; after which, he heard his Master say, That he was much surprized with somewhat that Mr. Lawe had told him.”

A witness was called, a Captain Wightman, “a person of good Reputation”. He testified that he had been a “familiar friend” of Wilson. The three men had been together that morning at the Fountain Tavern. That was an inn on the south side of the Strand, in the place now occupied by the restaurant Simpson’s-in-the-Strand. It was well-known for its kitchen and cellar 33 and was used by the Leicestershire men for their weekly Box dinners. “After they had staid a little while there,” the reporter continued, “Mr Lawe went away, after which Mr Wilson and Captain Wightman took Coach, and were drove towards Bloomsbury; whereupon Mr Wilson stept out of the Coach into the Square, where Mr Lawe met him.” The journey by coach was approximately half-a-mile. Law evidently did not possess a coach, or even the hire of one.

“Before they came near together, Mr Wilson drew his sword and stood upon his Guard. Upon which Mr Lawe immediately drew his Sword, and they both pass’d together, making but one pass, by which Mr Wilson received a mortal Wound upon the lower part of the Stomach, of the depth of two Inches, of which he instantly died.

“This was the Sum [total] of the Evidence for the King.” 34 Other witnesses supported Wightman’s account.

Who was this Captain Wightman, of good reputation? By far the best candidate is Joseph Wightman, who went on to be one of the great soldiers of his age. He rose through the ranks in the Duke of Marlborough’s wars, commanded a division of the Royal Army at Sherrifmuir during the Jacobite rising of 1715 and beat an invasion by Spanish forces in support of Highland Jacobites at Glen Shiel in western Scotland in 1719. A painting of that action by the Dutchman Peter Tillemans, now in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, shows Wightman on a prancing black horse amid the smoke and shot. He was much liked in Scotland for his decency. He died a major general, of apoplexy, at Bath in October, 1722. 35 An early life of John Law, a bookseller’s cuttings-job called The Memoirs, Life and Character of the Great Mr Law , described Wilson’s second in the duel as one “who is since a greater Man”. 36

That spring day of 1694, this Joseph Wightman was lieutenant and brevet-captain in the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards, the Grenadier Guards. 37 It is possible that he was of the Wightman family of Burbage, half a day’s ride from Edward Wilson’s Keythorpe, and that he had been a friend of Wilson’s since their childhoods in the county.

John Law then took the stand and said that “Mr Wilson and he had been together several times before the Duel was fought and never no Quarrel was betwixt them, till they met at the Fountain Tavern, which was occasioned about the Letters; and that his meeting with Mr Wilson in Bloomsbury was meerly an accidental thing, Mr Wilson drawing his Sword upon him first, upon which he was forced to stand in his own defence. That the misfortune did arise only from a sudden heat of Passion, and not from any Propense Malice.”

The judge instructed the jury that if they found the two young men

did make an Agreement to fight, though Wilson drew first, and Mr Lawe killed him, he was (by the construction of the law) guilty of murder: For if two men suddenly quarrel, and one kill the other, this would be but Manslaughter [punishable by a brand on the thumb]; but this case seemed to be otherwise, for this was a continual Quarrel, carried on betwixt them for some time before, therefore must be accounted a malicious Quarrel, and a design of murder in the person that killed the other. 38

Despite character witnesses “of good Quality” for Law, the jury followed the judge’s instruction and found him guilty of murder. He was condemned to hang along with a rapist/murderer and three counterfeiters, making three men and two women in all, after the close of the court session on April 20. (Transcript in Appendix I .)

Some thought Wilson’s family had bribed the jury. 39 In reality, the judge’s instructions were clear. The question which exercised London was not whether the killing was unlawful, but whether it was unfair. What mattered was not the law of the land but that of good society. 40

An examination of the scene and the Old Bailey Sessions Papers or court reports, though cold for three hundred years, is in Law’s favour. Law–Wilson was the only duel to come before the Old Bailey in the 1690s that took place in Southampton Square, while there were four in that decade in the fields behind Southampton House. 41 That was for good reason. The principal obstacle to duelling was the common public, and Southampton Square at 1 p.m. on a Monday would have been crowded, “a little toune”. 42 No doubt, the two young men agreed to meet at the top of the square for Wilson to leave his coach, whence they would proceed on foot into the wastes to the north. Yet, as Wightman testified, and the Judge accepted, Wilson instead got down and drew on Law. Law defended himself. There was just a single pass.

King William, impatient to leave on campaign in the Low Countries and occupied with reviewing troops in Hyde Park, reprieved Law. Law later wrote that that was through “the intercession of severall noblemen of Scotland”. 43 The Wilson family, led by the eldest brother Robert, Edward’s heir, believing the reprieve was prelude to a royal pardon, moved to organise their interest. 44 On April 22, a note was written into the Cabinet records: “Caveat that nothing pass relating to a pardon for John Laws . . . till notice first be given to Mr Robert Wilson, brother of the deceased, at his house in Stratton Street, Berkeley Square.” 45 (In English law, a caveat is an order filed with a court or minister to suspend a proceeding until opposition can be heard.)

Exploiting the mystery over Edward’s fortune and, perhaps, the below-the-belt wound, Robert set about convincing London and the King that death occurred not from his brother’s discourtesy to Mrs Lawrence, but from an armed robbery gone awry, “a Money business”. Wightman was probably by then out of the country on campaign and not around to deny it. Robert Wilson would hang Law by way of a civil prosecution, where the King and Queen had no power to pardon. On or about May 5, Wilson submitted an appeal of murder to the Sheriff of Middlesex, who had Law in custody at Newgate. The same day, after two false starts, King William left London and sailed from Margate on May 6.

Robert Wilson’s last will and testament, written at the end of 1726 and full of precise little legacies, reveals a man purse-proud, churchy and officious. He left a substantial property to his two surviving brothers, William and James, including estates at Keythorpe and Goadby in Leicestershire, at least £2,000 in securities, the building known as the Plough on the corner of Lombard Street and Change Alley in the City of London (which later housed Martin’s and then Williams and Glyn’s Banks), and two houses in Paternoster Row near St Paul’s Cathedral. To his brother-in-law, Charles Parker, he left “one shilling and no more”. 46

Robert Wilson was not without allies. His aunt, Mary Wilson, had married a leading West Country industrialist, Sir Joseph Ashe, and now a widow was living in state on the Thames at Twickenham. Their daughters had married into two rising Norfolk families, who were to be active in politics throughout the eighteenth century. Katherine Ashe in 1669 married William Windham of Felbrigg, and her dowry built the west front of the house and the orangery and planted the wood which is today at or some little past its prime. 47 Mary Ashe four years later married Horatio, Baron Townshend of Raynham, and their son Charles or ‘Turnip’ Townshend, part statesman, part improving farmer, was master of an unencumbered 20,000-acre estate yielding £5,000–£6,000 a year.

The appeal was set for May 9 at the Court of King’s Bench, an appeal court that had sat since the Middle Ages under the angel roof of Westminster Hall. For the hearing of the appeal, there are accounts from both sides. Thomas Carthew, acting for Law, left a report which was printed by his son. 48 William Cowper, later Lord Chancellor, who attended from beginning to end as a junior for Wilson, left a manuscript account now in the Hertford record office. 49 Law himself, in a letter to Queen Anne, said that Robert Wilson prosecuted the appeal “with great violence”. 50 From the surviving papers, that is the opposite of the truth.

On May 9, a Wednesday, Law was brought by the Sheriff of Middlesex from Newgate before the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Holt, and two fellow judges, Samuel Eyres and Giles Eyres. Representing him were Serjeants William Thomson and Clement Levinz and Carthew. In the first of many attempts at delay, Law’s counsel asked for extra time to prepare a plea to the writ. Throughout the case, at a time when jurists were still feeling their way in the common law, Holt wanted to ensure that both parties to the appeal should accept the judgment and went to great lengths to indulge the defence or appellee. “At last,” Cowper wrote, “upon much importunity & that the Appellee might have no colour of exception to the justice of the Court, the Appellee had two days time (viz.) till fryday next following given time to plead, so as he would stand by it.” 51 Law was taken away to the King’s Bench Prison, which occupied two houses on the east side of Borough High Street which ran down into Surrey from the only bridge over the Thames, London Bridge. 52

Like Newgate and, indeed, all prisons in England before the reforms of the nineteenth century, the Marshalsea of the Court of King’s Bench was a private enterprise. Granted as a freehold with its fees, profits and perquisites by James I in 1617, it had come into the possession of the Lenthall family of Oxfordshire. In 1682, William Lenthall mortgaged the office of marshal and some other assets to the merchant Sir John Cutler for £10,000 at a rate of interest of 5½ per cent per year. At some point, the debt increased to £18,000. 53

The consequence of this arrangement was that the Lenthalls had to squeeze out of the debtors and other prisoners and their families sufficient income to cover the interest on the mortgage and make a profit. This they did by selling the office of acting marshal to a succession of other men who, in turn, delegated the administration to favoured prisoners. A sort of caricature of the society outside its walls, the King’s Bench prison was divided into unequal sections: the Master’s Side, where prisoners with money might share rooms in a minimum of comfort and safety, and the Common Side, which does not bear thinking about. Those with money were fleeced for accommodation (“chamber rent”), discharge fees, beer, wine, food, bedding and exeats to the surrounding streets to ply their trades in the so-called Liberties of the King’s Bench. As Jonathan Swift wrote in “A Description of the Morning”:

The Turn-key now his flock returning sees

Duly let out a-Nights to steal for Fees.

The keepers solicited bribes to permit debtors to escape, which infuriated the creditors who had put them there. 54

For Lenthall and his servants, there was no incentive to maintain the buildings or keep the several hundred prisoners in health and, by 1754, the prison was so ruinous that it could no longer support either prisoners or mortgage, which had risen to £30,397 3s. 3d. The ministry decided to buy out the creditors and rebuild it. The lenders accepted 6s. 9d. on the pound from the Crown, or a loss to the face value of slightly under two-thirds. 55 It is just that a debtors’ prison should be bankrupt.

On the evening of May 9, when Law was admitted, the acting marshal was William Briggs, who had bought the post for life from Lenthall for £1,500 at Easter, 1690. He delegated his duties to John Farrington, a broken Haymarket victualler and prisoner for debt since at least 1677. Not much is known of those men, all of it bad. In November, 1690, the poor debtors had revolted against the Briggs-Farrington regime and petitioned Parliament, alleging that Farrington “doth barbarously oppress and extort upon the Petitioners, and causeth them to be put in lousy and stinking Rooms, except [unless] they sign a Book to pay extravagant Fees and Demands”. 56

When the House of Commons set up a committee of inquiry under Sir Jonathan Jennings, Briggs and Farrington beat up the witnesses. John Mallett, Esq.was dragged out from the Master’s Side and, “after several oaths, sworn by Mr Briggs, against this House, he was thrown into the common Ward, so dark and dank a Hole, that his Life, if not suddenly retrieved, is in Danger.” 57 Briggs was heard to say “they would do what they pleased with ther prisoners; for the Parliament had nothing to do with them” and, as for Jennings, “God damn Sir Jonathan Jennings, he did not care a fart for him.” 58 For that sally, Briggs was arrested by the serjeant-at-arms and forced to make “an humble Acknowledgement” of the offence to the House. 59

On Friday May 11, the court reconvened with Robert Wilson present. Law’s counsel again asked for time to plead, which Holt refused. Word of the duel had by now reached Scotland and the Lord Advocate, or attorney general, Sir James Steuart of Goodtrees, wrote for information to one of the Secretaries of State for Scotland in London, James Johnston of Warristoun.

On May 15, Johnston replied: “Mr Law’s Case is very doubtfull, all indifferent [impartial] Men are ag’t him, & I never had so many Reproaches for any Business since I knew England, as for concerning my Self for him: My Ld Ch Just [Sir John Holt,] is earnest to have his Life; the Archbp [John Tillotson, Archbishop of Canterbury] owns to me that he himself press’d the King not to pardon him, as being a Thing of an odious Nature, & which would give great Offence.” King William, before his departure, still favoured pardon. “The King said none had dy’d for Duells these many years, & the Law should be first reviv’d.” Johnston added: “He [Law] is in the King’s bench, & a Blockhead, if he make not his Escape, which he may easily do, considering the nature of that Prisson.” 60

On the 19th, for some reason Law was not in court, and Thomson raised an objection. Holt again permitted the objection, and the court rose until the following Monday, May 21, which happened to be the last day of the Easter term. That day, the court told Wilson’s counsel to prepare for a trial of murder “some time the beginning of the next Term” in the event that their appeal might be successful. 61

Fashionable London began to disperse. The duchesse de Mazarin, Charles II’s mistress, who was now living in retirement in Chelsea, wrote on May 31 to her young protégé, the Earl of Aran. “The fine youth have left on campaign, some at Windsor, and the others in Flanders.” 62

On June 9, the court returned and Law’s lawyers began to split hairs. On that day, and on June 22, they challenged the Latin writ, and every procedure in Law’s judicial treatment since the Old Bailey trial, on points of law and even Latin grammar and syntax. On each point, recorded by Cowper and Carthew in detail, the court responded that the defects did not obscure the common-sense meaning.

None the less, Holt was determined to be fair and, in recognition that Law’s life was in jeopardy (in favorem vitae ), gave the defence until the next term for further preparation, while again inviting Wilson’s team to make ready for the trial for murder. 63 Meanwhile the subscription books for the Bank of England were opened at the Mercers Chapel in Cheapside and, in twelve days of glorious sunshine, were filled. 64

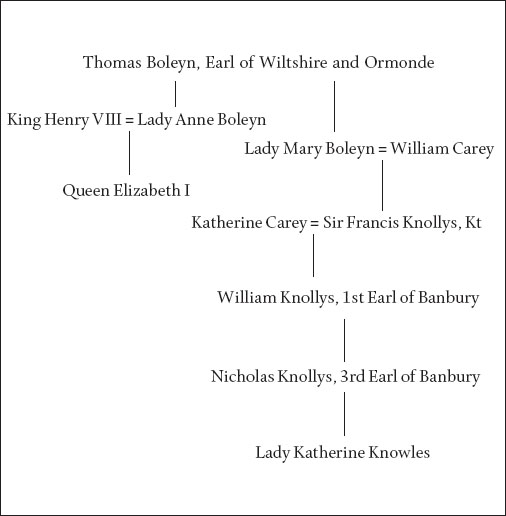

There was that Trinity Term before the King’s Bench Court one Charles Knollys, a name inscribed in the annals of English justice for a lawsuit, beside which Jarndyce v Jarndyce of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House is an instance of judicial panic. The Banbury Peerage case, which was first heard before the House of Lords in 1661 and for the last time in 1813, flared up in 1883 and may not even now be extinguished, has made much law in matters of adulterine bastardy, the rights of the English Peerage and the relation of the House of Lords to the courts.

Knollys was an unruly man whose once substantial family property consisted of “a bowling-green at Henley” in Oxfordshire. 65 He had married his wife in the Nag’s Head coffee house in James Street, Covent Garden and then wandered off with another lady to the continent. 66

In December, 1692, Knollys, then aged thirty, fought and killed his brother-in-law, Captain Philip Lawson and when arraigned at the Old Bailey on Saturday, December 10, pleaded misnomer. He was not Charles Knollys, Esq, but the 4th Earl of Banbury with a right to be tried by his peers in the House of Lords. 67

Flummoxed, the bench postponed the case to the next sessions. On January 17, 1693 the House of Lords rejected his petition for trial by his peers on evidence that his father was illegitimate. His case was transferred to the Court of King’s Bench where, in the spring of 1693, Holt granted him bail. There is no particular reason to believe that when Law arrived at the prison gate on May 9, 1694, he met his fellow duellist and gentleman, except this coincidence: Banbury’s sister, Lady Katherine Knowles (as she spelled her name) was the love of John Law’s life.

Lady Katherine was then about twenty-one years of age. 68 Those of a romantic turn may compose a love story in the manner of Dickens’s Little Dorrit (set in the Marshalsea Prison in the same street). Years later, in Paris, Lady Katherine was accused by Law’s enemies of acting the queen. The following pedigree does not excuse, but may explain such conduct:

As it turned out, Holt in that summer of 1694 took issue with the Lords, saying that that house had no more right to take away a peerage than it had to make one, and quashed the indictment. Amid such high reasonings, the bloody corpse of Captain Lawson was forgotten. Banbury walked free. What is probable is that Law’s acquaintance with Lady Katherine, first recorded on a French passport in 1702, must be brought forward some years. The Knollys family was in luck, for the daughter Lady Katherine bore to John Law stabilised their fortunes and preserved them to the present day.

By the end of October, Secretary Johnston was disgusted with both the case and Law’s languor and passivity. On the 30th, he wrote to Henry or Henrietta Douglas: “I am afraid Mr Law shall be hang’d at last, for I am in a Manner resolv’d to medle no more in the Matter: Had he his Senses about him, he had been out of Danger long before now.” In commenting on this letter in 1719, Johnston added: “No doubt the Jury agt’ him was bought I nether heard before nor after that killing a Man in a fair Duell was found Murther.” 69

On Saturday, November 3, Wilson’s counsel at last requested the murder trial should the appeal be accepted. Holt was infuriated and, in Cowper’s words, “rebuked the Attorny for not doing as he advised the last term when he tould him he might prepare for a Tryal at Barr the same day they should give j[udgment] on the Demurrer [Appeal] and that the Ve:fa [warrant] should have been returned on some past day of Return”. 70 The trial would have to wait. However, he ordered the prisoner to be brought up on the following Tuesday to hear judgment on the appeal.

That day, November 6, for the first time, Briggs brought in his prisoner in leg fetters. Law had tried to escape, according to young Cowper, “in the occasion past”, that is, on his return to prison from his last appearance on November 3. 71 The three judges unanimously dismissed all the defence’s objections. Holt said: “Appeal is the just right of a Subject not to be overthrown on too nice [hair-splitting] Exceptions.” The appeal was upheld and Law now faced the rope in the new year. 72 The tale of Johnnie Law, a Scotchman, who defied his wise mother and frittered away his inheritance, was coming to an end.

None the less, for all their pettifoggery, such a delight to critics of the common law, Law’s counsel had earned their fees. Three days later, November 9, after a frustrating campaign, King William landed at Margate and was at Kensington after dinner on November 10. 73

In 1719, by then in retirement and with Law famous, Secretary Johnston wrote down his recollections of the case for the British ministry. Those are of much less value than his copy-letters. As often happens so late after the event, his recollections compress the time elapsed, so that it is not at all clear when he is speaking of the spring of 1694 and when of the autumn: that is, before the King went on campaign in April or after he returned in November. A complication is that the diarist Narcissus Luttrell reports that the Duke of Shrewsbury was from at least November 20 “ill of a feavour”. 74

Johnston’s notes say that Law’s life had become a stumbling block in the fraught relations of Scotland and England or, as he called it, a “national Business”. He wrote that King William “had no quiet from the Townsend, and Ash, and the Windham’s Interest who were all cousin germains [first cousins] to Willson, who strangely prepossessed K Wm. When I reasoned the matter with the King, I was more rudely treated by him and the Nation [i.e. Scotland] too, than we had ever been on any Occasion.”

At the morning reception, known as the Levee, badgered by Johnston and one of the Scottish courtiers, Charles Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, 75 William made a false step. “It’s well known,” Johnston continued,

that talking to him at his Levy amongst other things I told him that it was hard to make Mr Laws suffer for his Ingenuity [honesty]; that without Mr Laws confession the ffact could not have been prov’d, for those that saw it being strangers to him when brought to Prison to see him, could only Swear that it was one like him. What [!,] said the K: Scotchmen suffer for their Ingenuity. Was ever such a thing known, added he, turning to My Ld Selkirk, who to do him Justice, was at the same time, seconding me in ffavour of Mr Law. Two or three more that stood next [near] heard it, and the Thing took Wind [got about] but with some pains I got the story suppress’d then. The next day being upon the same Subject, I told the K: the Scotch would not forget such an Expression. He said that I & Selkirk provok’d him to use it; but he wish’d he had not done it, and added cann’t you & he keep your own Secrets . . .

But that which stood most with him, & which he told me he could not but believe, was that Mr Laws want’d [was short of] Money, & that he had quarrell’d with Willson, who, he said, was a known Coward; in order to make him give him Money; All I could say to take of this signifi’d nothing.

At a loss, Johnston sought the aid of the first minister and Secretary of State, Charles Talbot, who had in April been elevated to the Dukedom of Shrewsbury and “had more Power then with the King, than any man alive”. Shrewsbury was doubtful, said King William was “mightily possess’d” against Law, but promised to keep the matter out of Cabinet for a week until Johnston could gain some proofs that it was not a “Money business”. Johnston sent to the City, to a Scots banker whose name he did not recollect, who offered to tell Shrewsbury that Law had just received from Scotland a bill or credit of £400. The Duke was satisfied but reported that the King would not pardon Law “without the friend’s [Robert Wilson’s] consent; tho’ added he, I think the K: is willing he should be saved, provided it can be done in such a Manner as that his Majtie did not appear in it, nor must I said the Duke of himself.” 76